Online Seminar

Spring 2020

AA, The Architectural Association School of Architecture, London

With Meggie Kelley, Shawn Maximo, Soft Baroque and Dan Handel

Interior Comforts is an online seminar by Matylda Krzykowski, in context of AA Speculative Studies, initiated by Eva Franch, exploring issues of contemporary culture through the study of other disciplines and practices and their relation to architecture.

INTERIOR COMFORTS, SPATIAL DISORIENTATION

Written by Nour Hamade, a participating student. PDF by Nour Hamade.

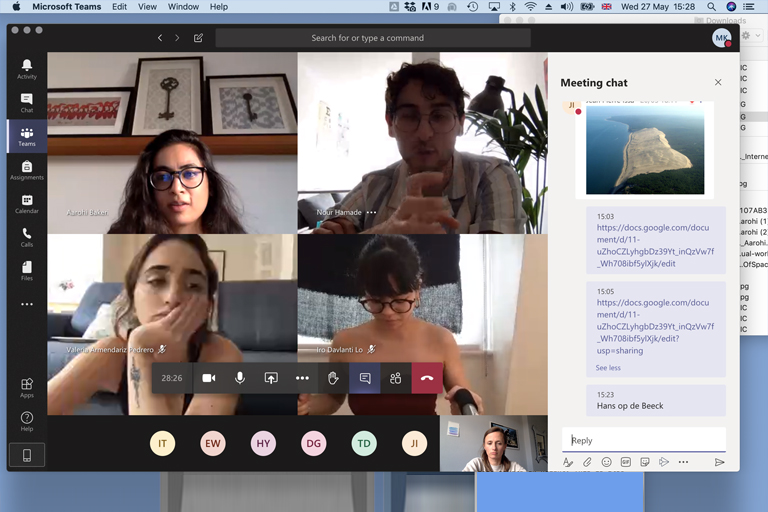

An opinionated description on the seminar series ‘Interior Comforts’ by Matylda Krzykowski fulfilled through Microsoft Teams during COVID-19 from 29th of April 2020 with a final online ‘exhibition’ launched on the 16th of June 2020, via the AA School Instagram.

Day forty-seven

I woke up today

I haven’t left the house in six days

It’s grey again

I look around my room

White surfaces

Colourful objects

It’s grey again

The idea of home

Filled with its paradoxes

Its omnipresence – I neglect it

It’s grey again

April 28th; 15:58 BST – An introductory task by e-mail set by Matylda Krzykowski within the context of Meggie Kelley’s architectural writings on cosiness: ‘Your assignment for tomorrow is to write down thoughts and ideas in bullet points about what comfort and cosiness is. There is no right or wrong, you can of course take it from the idea of an interior, but you can also take it further into political, social, or general aesthetic terms’:

My bulletpoints: • Home • Hygge • Warmth • State of mind • Safety • Acceptance • Being free and able to express yourself – the freedom of movement (or the lack of) • People • Objects • Mental Subjectivity • Physical Subjectivity • What it is NOT: worry and fear • Gestures • Seduction

We ‘met’ for the first time on the 29th of April, with Matylda introducing the seminar series, guest lecturers, expectations and the outcome of the course. By the first hour, we were joined by architect and writer Meggie Kelley. Kelley’s work focuses on humanism and materialism, where she rediscovers the ‘feeling of things’ within architectural history. Within the lecture, Kelley gave us an analytical description on the concept of snug spaces, focusing on the alcove. She explains “snug spaces are often defined as compact and close fitting. In other words, small enough to promote a sense of privacy, but large enough to feel at ease,”(1) giving a sense that a snug space lies somewhere perfectly in between two ideals. The recurrent reference to ‘cosiness’ was fascinating in retrospect to my preceding understanding of comfort. She described the theory of cosiness in its ambiguous nature, warning us on its association with the bourgeois and its established association. Like comfort, cosiness cannot and should not be interpreted as uniform or standardised, therefore, cannot be fixed.

What is comforts Interior?

Every time ‘comfort’ came to mind – I so unwillingly thought of home. But why? The term ‘comfort’ suggests a notion of ease and an easiness – to be comfortable is, essentially, to be at ease with one’s environment. To be comfortable is to put strenuous efforts in order to distinguish where the body ends and where the world begins; it is essentially a disregard to one’s surroundings. When one overlooks things – when nothing seems to be out of (ones) ordinary. When all adjacent objects transcend into the background.

The aim of Speculative Studies was to “test new educational formats and alternative methods of teaching and learning.”2 Encompassing prevalent issues within contemporary cultures, Eva Franch i Gilabert, the AA’s director at the time, introduced the new ‘core studies’ as a way to tackle architecture and its inter-disciplines. With the additional challenge of worldwide confinement, we were to have the course from the comforts of our own homes. As Matylda stated; “the intent of the seminar is to practice the visualisation, improvisation and production of alternative interior elements in order to develop ideas around comfort.” How to live?(3) She asks. How do I live? Where, what, why, with who? The course included fifteen students, three of which were from the diploma school (including myself). As a fourth year during the course, it was an additional elective that was not mandatory, though, there was something striking about this idea of learning about interiors whilst being forced to remain in (only) one.

Instructions given include (but are not limited to):

• not to think about the spatial elements of domesticity

• to forget about the home

• to forget about furniture

• to forget about the goals of different element

so, ultimately, to concur an interruption on our memory of space, domesticity and comfort. Matylda references the 1997 film series ‘Men in Black’, where Will Smith and Tommy Lee Jones use a ‘Neuralyzer’ that has the ability to wipe the mind of anybody.

Taxonomy; the act of classifying. Within architecture, taxonomy is the act of naming spaces, objects and people as functions. A ‘kitchen’, ‘bedroom’, ‘bathroom’ or ‘lounge’ demonstrates the function that will occur in the labelled space, hence, already limiting the user’s ability and use of such (space). Architects classify the design of their spaces in order to easily understand how their designs function; understandingly, it aids designers in creating functional spaces with a pre-set use, therefore, designing the correct space for the correct use. We study architecture, our entire education is based on the specific roles of the floor, the wall, the roof.

We are taught to believe that there are standards for comfort. Set guidelines that would ultimately create a ‘comfortable’ space: the specific volume of a room, the size of an opening, the materials and colours of the surfaces that surround us, the proportions of objects that allow us to sit, eat, sleep, or even pee comfortably. Soft Baroque4 is made up of design duo Nicholas Gardner and Saša Štucin, who were a part of our second seminar, exploring the (anti) roles of furniture and objects. Their projects explore and blur the boundaries between acceptable furniture typologies and conceptual representative objects. Within the seminar, we explored living structures, things that are atypical; objects, furniture, products or systems that exist outside the norm. Soft Baroque’s work scrutinizes the interrelations between furniture, graphic design, ‘objecthood’ and the perception of materiality within the digital age. I found a project by Mona Hatoum, a Lebanese artist, untitled, that depicts a wheelchair made out of stainless steel. Object, comfort and use; the piece demonstrated the relationship between comfort and use – the ways in which function can be made redundant when comfort is absent. This led to a discussion on the use of materiality within comfort, and the depiction of comfort as a somewhat tangible (or transcribed) object.

Is it pleasure?

This is when it is worth differentiating between comfort (physical) and comfort (mental/state of mind). Physical comfort can usually be pre-determined by ergonomic forms, physical attributes and standard human behaviour; these are factors such as size, material, light and temperature. A mental comfort is subjective to each body, which relates more to memory, people and objects; a personal preference. “Pleasure awakes new understandings of reality, while comfort numbs us.”(5) We tend to associate comfort with pleasure – commonly understanding it as a positive indicator. In architecture, “comfort is normally related to bodily experience in terms of sensory relaxation.”(6) I like to think of comfort as being orientated, as so that when you are uncomfortable, that is merely a reaction of being disorientated. Bodies that experience discomfort or disorientation can be defensive. Their bodies react to a form of conservative politics that are exhibited in their gestures – gestures that seek to re-ground themselves. Comfort and cosiness are a state of mind – they are personal subjectivities that cannot be pre-determined. Spaces are a continuation of ourselves, they are like a second skin that “unfolds in the folds of the body”7 – spaces are not exterior to the bodies.

How does it turn into discomfort?

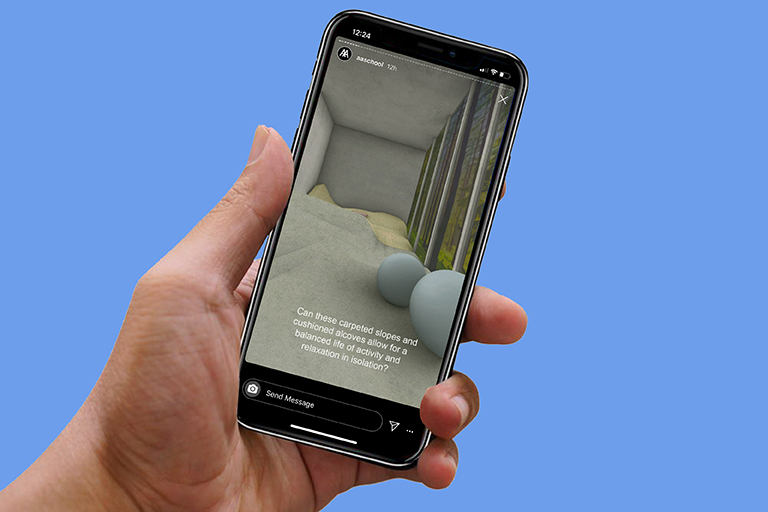

The objective of the seminar was an ‘online’ exhibition, covering the spatial intentions of the fifteen participating students on the ideal space of confinement. Matylda asks: “consider practical, physical and psychological understandings of what you expect from an interior and design an indoor space to survive by determining space requirements and selecting essential and additional items, such as shapes, colours, lighting, and materials, among others.”

When I was forced to think of a space that I would ‘like’ to be isolated in – I was blank. I could not think of comfort as a tangible object, or even a space. All I wanted was freedom. Although it was difficult to think of the ideal space of comfort, I began by essentially thinking of the most uncomfortable space I could potentially be in. A confined, definitive space in an absolute position and location in space that limits motility and freedom. An enclosed volume where one cannot manipulate their sense of orientation, one where creativity is interrupted and imagination is obstructed. Fixed layouts and unadaptable objects impose a standstill – halting time. They develop a sense of disorientation as the body and the mind are forced to function at a limit – a limit foisted by the space itself. In regards to Soft Baroque’s emphasis on materiality, interchangeable textures and limitless typologies, I had a contradictory thought; a space with no (obvious) materials, no textures, no prescribed reactions – not necessarily a colourless environment, but one that can be created by the user, during their experience. The space I finally designed was a material-less, wall-less (open), declassified (functionless or adaptable) environment. I placed a curtain (a piece of material that acts as a screen) on one ‘side’ of the volume in order to create a sense of orientation – a physical sense of direction navigates a sense of safety, where the body’s position incorporates a sense of perspective on/to other places. The space was surrounded by what we can describe as a ‘green screen.’ It was used as a tool to alternate between ‘scenes;’ where the conditions of the environment are interchangeable, adaptable and distinct. From the beach, to the mountains, to the inner city, it was a choice given to the individual confined within (myself). I named the space: ‘The Controlled Odyssey’ – a paradox, yes.

Can transience be permanent?

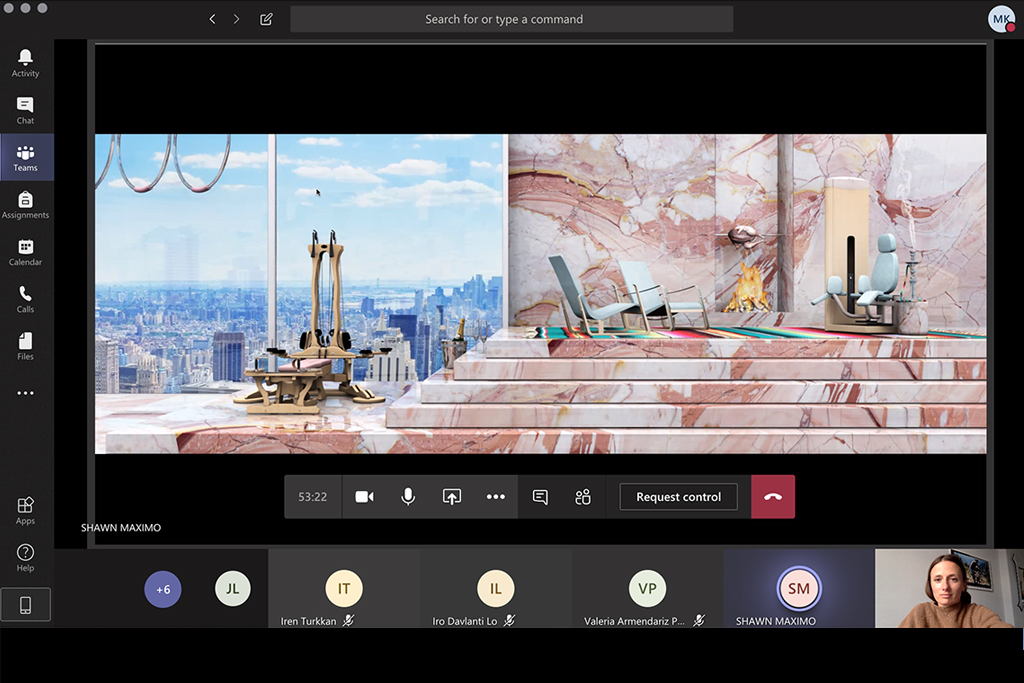

Shawn Maximo(8) presented his architectural dioramas and spatial hybrids for the first time through a video call. Most of Maximos’ presentation posed ‘what if’ scenarios, which greatly inspired my understanding of space and confinement. Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau: A 21st Century Show Home at the Swiss Institute exhibition by Felix Burrichter(9) – where Maximo designed the exhibition – had numerous objects and spaces placed in a large green screen space, which allowed viewers to create scenes with the exhibited objects. As an architectural tool that gave the visitor the power and creative control, I sought to uncover how that control would be primal within my own space. A virtual reality within a world that seemed to be disintegrating sounded nice – some relief from the ongoing pain. As I recollect my spatial intentions, I now think of how I subconsciously thought of an adaptable environment without recollection of Maximo’s work; his work captivated my views on transient (permanent) space.

To further challenge the role of taxonomy, Dan Handel10 discussed his work ‘Carpet Space’. A project that challenges aesthetic and performance – the role of a carpet, the floor, and the possible relationships between carpets and their architectural hosts. The project exposes the links between “optics, technology, body politics, and space,” further challenging the economy of consumption. Uncovering the relevance and the authentic role of the floor, I began re-questioning the rules of taxonomy that we were taught within school. If I was to break through the necessary functions of a floor, a wall or a roof, I could then envision surfaces – simply planes. This led to a design decision which took such surfaces as floating devices that could be used in every which way, functional or ornate. Within the seminar, Handel exclaimed: “happy accidents and banal questions are a great start to any project;” posing the question “what kind of rituals do you want in your space?” I decided to design and construct a sort of manual – a how-to (use) tool for the space.

The Controlled Odyssey User Manual: The feeling of confinement or entrapment can make one feel uneasy and ‘uncomfortable,’ therefore, the space serves to allow the body to move freely and operate without boundaries, whilst still bound within a space.

To use the space, you must;

i. Leave your worries and imagine yourself in a happy place, wherever that might be.

ii. You, only you, are in control of your body in this space – everything within is there to serve you.

iii. or do nothing – space is there to allow you to be you. iv.Infinite surfaces allow you to be surrounded by comfort – things, objects or memories that allow you to reminisce, reorientate, and recreate ‘serenity.’

v. Comfort as you please.

As the seminar series came to an end, we finally presented the fifteen students’ work via 69 stories on Instagram, conveying our interior comforts through a 5.8 inch screen. With everyone scattered around the globe, we were able to exploit the digital world by allowing people within the school (and strangers) into our sacred spaces and ideas of comfort. It was worth questioning the future (and current) architects of the spaces of which we inhabit everyday and how they should adhere to the role of comfort. The role of comfort in respect to the body’s and mind’s experience.

Ending with Michael Sorkin’s quote from a text we had read in the seminar, Comfort: reclaiming place in a virtual world “the danger after all is not in the measurements of private pleasures, but in a universal standard, comfort fits all.”(10)

Finally, thank you Matylda for forcing me to test the parameters of comfort and for the opportunity to write about it.

Footnotes:

1 Kelley, M., (2014). Dark Alcoves, Hidden Niches, and Cozy Corners. New York: Circadian Press. p. 47

2 AA School, (2020). Experimental Programme: Core Studies. Architectural Association. Accessed 3 September 2020. https://www.aaschool.ac.uk/ academicprogrammes/experimental

3 Fundaments from the practice of the artist Andterea Zittel

4 Soft Baroque, (n.d.). Work: Superbench. Accessed 22 September 2020. https://softbaroque.com/superbench

5 Esteve, P., (2017). ‘Wake Up Call: architectural comfort in the age of passivity’, PIN-UP, 23.

6 Ibid.

7 Ahmed, S., (2006). Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 134

8 Maximo, S., (n.d.). Shawn Maximo Studio. Accessed 22 September 2020. http://shawnmaximo.com/Home. aspx

9 Carpenter, W., (2015). ‘21st-Century L’Esprit Nouveau: PIN–UP’s Felix Burrichter wows us with a must-see Swiss Institute exhibition’, Pamono. (Online Article). Accessed 24 September 2020. https://www.pamono. co.uk/stories/21st-century-lesprit-nouveau

10 Handel, D., (2019). Project: Carpet Space. Accessed 22 September. http://www.handandel.com/carpet-space

11 Sorkin, M., (2001). Comfort: Reclaiming Place in a Virtual World. Cleveland: Cleveland Center for Contemporary Art. p. 14

12 Hatoum, M., (1998). Untitled (wheelchair). Tate. Accessed 6 May 2020. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/ hatoum-untitled-wheelchair-t07497